Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Corbis via Getty Images

Corbis via Getty ImagesDuring the winter of 1956, the Times correspondent, David Holden, arrived on the island of Bahrain, then still a British protectorate.

After a short -term career of geography, Holden had impatiently waited for his Arab assignment, but he did not expect to attend a Durbar garden in honor of the appointment of Queen Victoria as an imperative of India.

Wherever he went to the Gulf – Dubai, Abu Dhabi and Oman – he found expected traces of British India.

“The RAJ maintains here a slightly whimsical influence”, wrote Holden, “a situation rich in anomaly and anachronism … The servants are all carriers, the linen a dhobi, and the goalkeeper a chowkidar”, he wrote, “on Sunday, the guests are confronted with an ancient curry lunch, and acceptable and Anglo

The Sultan of Oman, educated in Rajasthan, spoke more commonly in Ourdou than Arabic, while soldiers of the neighboring state of that Etiti, now Oriental of Yemen, worked in uniforms of the Hyderabadi army now disappeared.

In the words of the governor of Aden himself:

“One had an extraordinarily powerful impression that all the clocks here had stopped seventy years ago; that the Raj was at its height, Victoria on the throne, Gilbert and Sullivan a fresh and revolutionary phenomenon, and Kipling a dangerous beginning, was so strong the link of Delhi via the Hyderabad to the South Shore.”

Although largely forgotten today, at the beginning of the 20th century, nearly a third of the Arabian peninsula was judged as part of the British Indian Empire.

From Aden to Kuwait, a crescent of Arab protectorates was governed by Delhi, supervised by the Indian political service, controlled by Indian troops, and responsible for the viceroy of India.

Under the 1889 interpretation law, these protectorates had all been legally considered as part of India.

The standard list of semi-independent princely states of India as Jaipur opened in alphabetical order with Abu Dhabi, and the vice-king, Lord Curzon, even suggested that Oman is treated “as much an indigenous state of the Indian Empire as Lus Beyla or Kelat [present day Balochistan]”.

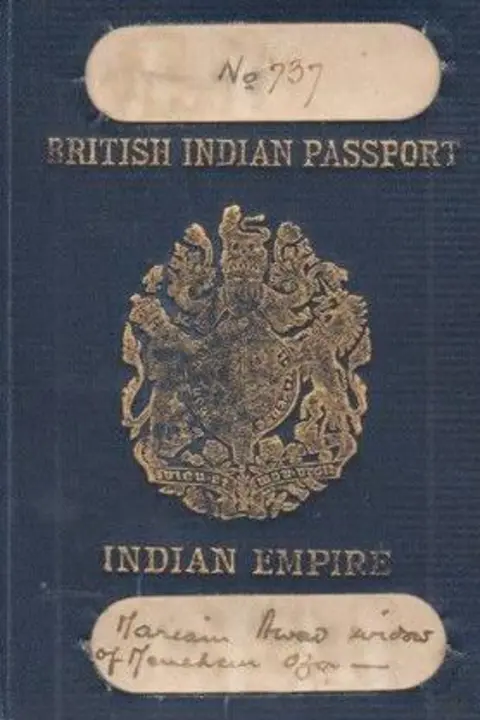

Indian passports have been issued as far to the west as Aden in modern Yemen, which worked as the west west port and was administered as part of the province of Bombay. When Mahatma Gandhi visited the city in 1931, he found many young Arabs identifying himself as Indian nationalists.

Royal Geographical Society via Getty Images

Royal Geographical Society via Getty ImagesEven at the time, however, few members of the British or Indian public were aware of this Arab extension of the British Raj.

Cards showing the complete scope of the Indian Empire were only published in secrecy, and the Arab territories have been left public documents to avoid causing the Ottomans or later the Saudis.

Indeed, like a lecturer of the Royal Asiatic Society joked:

“As a jealous sheikh veils his favorite wife, therefore the British authorities envelop the conditions of the Arab states in a mystery as thick as the badly disposed propagandists could almost be excused for having thought that something terrible happens there.”

But in the 1920s, politics changed. Indian nationalists have started to imagine India not as an imperial construction but as a cultural space anchored in the geography of Mahabharata. London has seen the opportunity to redraw borders. On April 1, 1937, the first of several imperial partitions was promulgated and Aden was separated from India.

A telegram from King George VI was read out loud:

“Aden has been an integral part of the British Indian administration for almost 100 years. This political association with my Indian Empire will now be broken, and Aden will take its place in my colonial empire.”

However, the Gulf remained within the reach of the government of India for another decade.

British officials briefly discussed the question of whether India or Pakistan “would be authorized to manage the Persian Gulf” after independence, but a member of the British Legation in Tehran even wrote from his surprise “apparent unanimity” of “officials in Delhi … that the Persian Gulf was little interested in the government of India.”

As William Hay, the resident of the Gulf said, “it would have clearly been inappropriate to put the responsibility of treating the Arabs in the Gulf to the Indians or the Pakistanis”.

The Gulf States, from Dubai to Kuwait, were therefore finally separated from India on April 1, 1947, months before the RAJ itself was divided into India and Pakistan and granted independence.

Sam Dalrymple

Sam DalrympleMonths later, when Indian and Pakistani officials began to integrate hundreds of princely states into the new nations, the Arab States of the Gulf would lack the big book.

Few struck an eyelid and 75 years later, the importance of what had just happened is still not fully understood in India or in the Gulf.

Without this minor administrative transfer, it is likely that the States of the Persian Gulf residence would have been part of India or Pakistan after independence, as has happened to all other princely states of the subcontinent.

When British Prime Minister Clement Attlee proposed a British withdrawal from the Arab territories at the same time as the withdrawal of India, he was shouted. Great Britain has therefore retained its role in the Gulf for 24 more years, with an “Arab Raj” reporting now to Whitehall rather than the vice-king of India.

According to the words of the Gulf Paul Rich scholarship holder, it was “the last redoubt of the Indian Empire, just as Goa was the last lonely vestige of Portuguese India, where Pondicherry was the label of French India”.

The official currency was still the Indian rupee; The simplest mode of transport was still the “Line British India” (Maritime Company) and the 30 Arab princely states were still governed by “British residents” who had made their careers in Indian political service.

The British finally did not withdraw from the Gulf in 1971 as part of his decision to abandon the colonial commitments east of Suez.

As David Holden wrote in July:

“For the first time since the peak of the British Society of East India, all the territories around the Gulf will be free to seek their own salvation without the threat of a British intervention, or the comfort of British protection. The latter remains of the British Raj – for that, in fact, anachronism … But its day is over.”

Of all the national stories that emerged after the collapse of the Empire, the Gulf States have managed the most to erase their links with British India.

From Bahrain to Dubai, a past relationship with Great Britain is recalled, but Delhi’s governance is not. The myth of ancient sovereignty is crucial to maintain the monarchies alive. However, private memories persist, in particular the unimaginable reversal of the classes that the Gulf has seen.

In 2009, the scientist of the Gulf, Paul Rich, recorded an elderly Qatari gentleman who “has always got angry when he told me about the blows he received when, as a young boy of seven or eight, he stole an orange, a fruit that he had never seen before, to an Indian employee of the British agent”.

“The Indians,” he said, “were a privileged caste during his youth, and it gave him an immense pleasure that the tables have turned and they have now come to the Gulf as servants.”

Today, Dubai, formerly a minor outpost of the Indian Empire without salvation of firearms, is the sparkling center of the new Middle East.

Few millions of Indians or Pakistanis who live there know that there was a world in which India or Pakistan could have inherited the Gulf rich in oil, just as they did Jaipur, Hyderabad or Bahawalpur.

A silent bureaucratic decision, taken at the twilight of the Empire, cut this link. Today, only the echoes remain.

Sam Dalrymple is the author of Shattered Lands: Five Scores and the Making of Modern Asia