Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

The head lice, the chips and the tenias were the companions of humanity throughout our evolutionary history. However, the largest parasite in the modern era is not an invertebrate of blood. It is elegant, in glass and addictive by design. His host? Each human on earth with a WiFi signal.

Far from being benign tools, smartphones are slowing down our time, our attention and our personal information, all in the interest of technological companies and their advertisers.

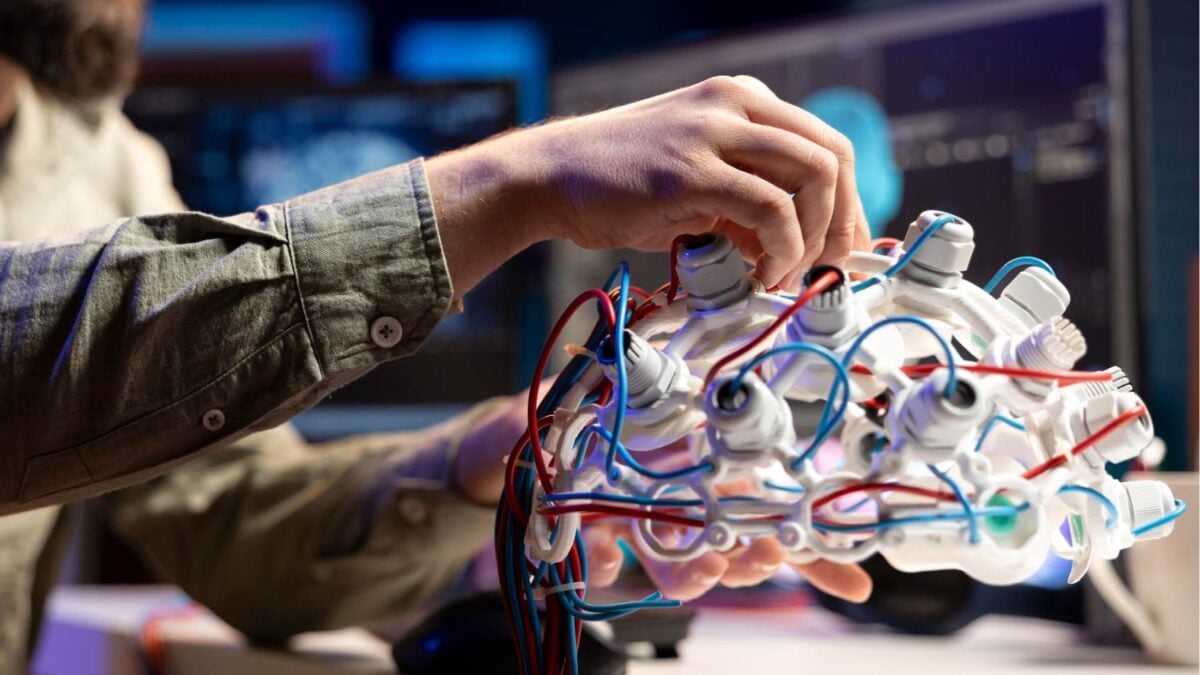

In a new article in the Australas journal of philosophyWe argue that smartphones pose unique societal risks, which are strongly concentrated through the objective of parasitism.

Evolutionary biologists define a parasite as a species that benefits from a close relationship with another species – its host – while the host has a cost.

THE thumbFor example, depends entirely on our own species for its survival. They only eat human blood, and if they were dislodged from their host, they only survive briefly unless they have the chance to come across another human scalp. In exchange for our blood, the head lice give us only itching; This is the cost.

Smartphones have radically changed our lives. From the navigation of cities to the management of chronic health diseases like diabetesThese pieces of pocket technology facilitate our lives. So much so that most of us are rarely without them.

However, despite their advantages, many of us are hostage to our phones and slaves with endless parchment, unable to disconnect completely. Phone users pay the price With a lack of sleep, lower offline relationships and mood disorders.

Not all the narrow relationships of species are parasitic. Many organizations that live or in us are beneficial.

Consider bacteria in the digestive animals of animals. They cannot survive and reproduce only in the intestine of their host species, feeding on passing nutrients. But they offer In the host, including improved immunity and better digestion. These win-win associations are called mutualism.

The Human-Smartphone Association began as a mutualism. Technology has proven to be useful for humans to stay in touch, navigate via cards and find useful information.

Philosophers have spoken of it not in terms of mutualism, but rather than phones being a Extension of the human mindLike notebooks, cards and other tools.

From these benign origins, however, we argue that the relationship has become parasitic. Such a change is not of a rare nature; A The mutualist can evolve to become a parasiteor vice versa.

As smartphones have become almost essential, some of the most popular applications they offer have come to serve the interests of application companies and their advertisers more faithfully than those of their human users.

These applications are designed To push our behavior to Keep us scrollingClicking on advertising and simmering in perpetual indignation.

The data on our scrolling behavior is used to continue this operation. Your phone only cares about your personal fitness goals or your desire to spend more time with your children since it uses this information to adapt to better capture your attention.

It can therefore be useful to think of users and their phones like hosts and their parasites – at least part of the time.

Although this awareness is interesting in itself, the benefit of seeing smartphones through the evolutionary objective of parasitism takes on its full role when the relationship could then be headed – and how we could thwart these high -tech parasites.

On the major reef barrier, Bluestreak Cleaner Wrasse Establish “cleaning stations” where the largest fish allow the wrasse feeding on dead skin, bulk scales and invertebrate parasites living in their gills. This relationship is a classic mutualism – the biggest fish lose expensive parasites and the cleaner wrasse is nourished.

Sometimes, cleaner cleaning “cheat” and stifle their hosts, turning the scale of mutualism to parasitism. The cleaned fish can punish offenders by chasing them or holding other visits. In this, reef fish have something that evolutionary biologists see as important to maintain the balance in balance: the police.

Could we adequately control our exploitation by smartphones and restore a Net-Beneralized relationship?

The evolution shows that two things are essential: an ability to detect the exploitation when it occurs and the ability to respond (generally by removing the service to the parasite).

In the case of the smartphone, we cannot easily detect the operation. Technological companies that design the various features and algorithms to allow you to get your phone This behavior do not advertise.

But even if you are aware of the nature of exploitation of smartphone applications, the answer is also more difficult than simply putting the phone.

Many of us have become dependent on smartphones for daily tasks. Rather than remembering the facts, we unload the task to digital devices – for some people, This can change their cognition and memory.

We depend on having a camera to capture life events or even record where we parked the car. This The two improve and limit our memory of events.

Governments and businesses have no longer cemented our dependence on our phones, by moving their online services via mobile applications. Once we have won the phone to access our bank accounts or access government services, we have lost the battle.

How then can users repair the unbalanced relationship with their phones, by putting the parasitic relationship into a mutualist relationship?

Our analysis suggests that the individual choice cannot be reliable. We are individually exceeded by the enormous advantage of information companies that technological companies hold in the host-the-parasitic arms race.

The Australian government Ban of minor social media is an example of the type of collective action necessary to limit what these parasites can do legally. To win the battle, we will also need restrictions on Characteristics of the application known to be addictiveand on the collection and sale of our personal data.![]()

Rachael L. BrownDirector of the Center for Philosophy of the Science and Associate Professor of Philosophy, Australian National University,, And Rob BrooksProfessor of science evolution; Unsw Sydney

This article is republished from The conversation Under a creative communs license. Read it original article.