Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

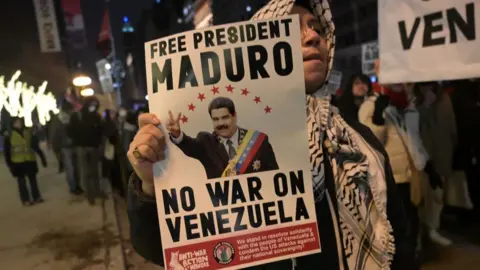

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOn Monday morning, Nicholas Maduro, handcuffed and wearing a jumpsuit, stepped off a military helicopter in New York, flanked by armed federal agents.

The Venezuelan president had spent the night in a notorious federal prison in Brooklyn, before authorities transported him to a Manhattan courthouse to face criminal charges.

Attorney General Pam Bondi said Maduro was brought to the United States to “face justice.”

But international law experts question the legality of the Trump administration’s actions and say the United States may have violated international laws governing the use of force. Domestically, however, U.S. actions fall into a legal gray area that can still lead to Maduro facing trial, regardless of the circumstances that brought him there.

The United States maintains that its actions were legally justified. The Trump administration has accused Maduro of “narcoterrorism” and allowing the transportation of “thousands of tons” of cocaine to the United States.

“All personnel involved acted professionally, decisively and in strict accordance with U.S. law and established protocols,” Bondi said in a statement.

Maduro has long denied U.S. allegations that he was overseeing an illegal drug operation, and in New York court on Monday he pleaded not guilty.

Although the charges focus on drugs, the U.S. prosecution of Maduro comes after years of criticism from the broader international community of his leadership in Venezuela.

In 2020, UN investigators said Maduro’s government had committed “gross violations” amounting to crimes against humanity – and that the president and other top officials were involved. The United States and some of its allies have also accused Maduro of rigging the election and have not recognized him as the legitimate president.

Maduro’s alleged ties to drug cartels are at the center of this legal case, but the methods used by the United States to bring him before an American judge to face these charges are also under scrutiny.

Carrying out a military operation in Venezuela and driving Maduro out of the country under the cover of darkness was “completely illegal under international law”, said Luke Moffett, a professor at Queen’s University Belfast’s law school.

Professor Moffett and other experts have highlighted a host of problems raised by the US operation.

The United Nations Charter prohibits its members from threatening or using force against other states. It allows “self-defense in the event of armed attack”, but that threat must be imminent, Professor Moffett said. The other exception occurs when the UN Security Council approves such action, which the United States did not obtain before acting in Venezuela.

International law would view the drug trafficking offenses that the United States accuses Maduro of as a matter of law enforcement, experts say, not a violent attack that could justify one country taking military action against another.

In public statements, the Trump administration has characterized the operation, in the words of Secretary of State Marco Rubio, as “essentially a law enforcement function,” rather than an act of war or military campaign.

Maduro has been charged with drug trafficking in the United States since 2020; The Justice Department has now issued a higher – or revised – indictment against the Venezuelan leader. The Trump administration is essentially saying it’s now enforcing it.

“The mission was conducted to support ongoing criminal prosecutions related to large-scale narcotics trafficking and related offenses that have fueled violence, destabilized the region, and directly contributed to the drug crisis that has cost American lives,” Bondi said in his statement.

But since the operation, several legal experts have said the United States violated international law by expelling Maduro from Venezuela on its own.

“A country can’t go to another foreign country and arrest people,” said Milena Sterio, an international criminal law expert at Cleveland State University School of Law. “If the United States wants to arrest someone in another country, the right way to do it is extradition.”

Even if an individual is charged in the United States, “the United States does not have the right to travel around the world to enforce the arrest warrant on the territory of other sovereign states,” she said.

Maduro’s lawyers in Manhattan court said Monday they would challenge the legality of the U.S. operation that transported him from Caracas to New York.

There is also a long-standing legal debate over whether presidents must follow the United Nations Charter. The U.S. Constitution considers treaties entered into by the country to be the “supreme law of the land.”

But there is a clear historical example of a presidential administration claiming that it was not required to comply with the charter.

In 1989, the administration of George HW Bush deposed Panama’s military leader, Manuel Noriega, and brought him to the United States to face drug trafficking charges.

An internal Justice Department memo at the time asserted that the president had the legal authority to order the FBI to arrest individuals who violated U.S. law, “even if those actions contravened customary international law” — including the United Nations Charter.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe memo’s author, William Barr, became U.S. attorney general during Trump’s first term and brought the original indictment against Maduro in 2020.

However, the memo’s reasoning was later criticized by legal scholars. American courts have not explicitly ruled on the issue.

In the United States, the question of whether this operation violated any domestic law is complicated.

The U.S. Constitution gives Congress the power to declare war, but puts the president in charge of the armed forces.

A Nixon-era law, called the War Powers Resolution, places restrictions on the president’s ability to use military force. It requires the president to consult with Congress before sending U.S. troops abroad “in every possible case,” and to notify Congress within 48 hours of the deployment of forces.

The Trump administration did not notify Congress before the action in Venezuela “because it endangers the mission,” Rubio said Saturday.

However, several presidents have tested the limits of their powers to order military actions without congressional approval, and Trump has been carrying out military strikes against suspected drug boats in the Caribbean for months, despite bipartisan criticism.

US federal courts now have jurisdiction over Maduro, regardless of how he arrived.

Maduro could claim that the United States violated international laws by forcibly taking him to New York. But numerous legal precedents suggest a trial against Maduro would take place, Professor Sterio said.

“Our courts have long recognized that for a defendant, even if he or she is kidnapped or forcibly taken to the United States, that is not grounds to dismiss the case,” she said.