Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

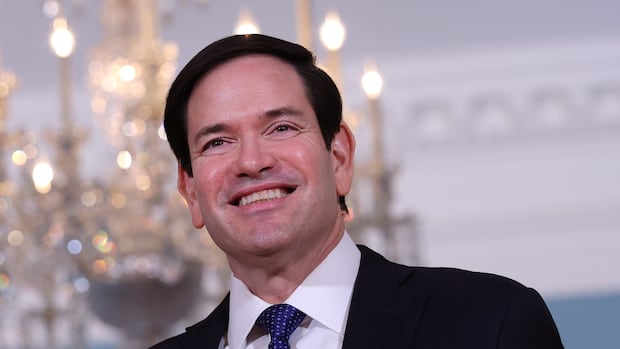

When Marco Rubio spoke at Mar-a-Lago shortly after U.S. President Donald Trump announced that the country had captured Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, it was the culmination of a decade of effort by the secretary of state and a clear sign that he had become a leading voice within the Trump administration.

The bold one – and potentially illegal — An overnight operation saw more than 150 US planes fly over Venezuelan airspace as Delta Force commandos stormed Maduro’s home, seizing the leader and his wife before exfiltrating the couple to New York. They face multiple charges, including narcoterrorist conspiracy, cocaine importation conspiracy and weapons possession. They have pleaded not guilty to all charges.

At Mar-a-Lago, Rubio said the message was clear: “Don’t play games with this president in office, because it’s not going to go well.”

But his deferential comments belie the outsized role he likely played in the call to action in Venezuela.

Rubio, 54, the son of Cuban immigrants, grew up in Miami, steeped in Cuban culture and the anticommunist sentiments shared by many in the community.

He has “lived experience,” said Matthew Bartlett, a Republican strategist and State Department appointee during Trump’s first term.

As a senator representing Florida, Rubio took a keen interest in the affairs of Latin and South America.

In 2017, he spoke in the Senate and called Maduro a dictator, urging foreign companies and governments not to do business with Venezuela.

It was just one of many instances where he used his senatorial pulpit to denounce what he saw as Maduro’s regime of “repression.”

During Trump’s first term, Rubio became a key figure, helping to guide U.S. policy in the region. It was a surprising turnaround after a sometimes rocky relationship on the campaign trail, when the two were seeking the Republican nomination in 2016.

In 2019, he co-sponsored a bill aimed at restoring democracy to Venezuela and accelerating planning for the country’s financial institutions after Maduro.

Six years later, it is unclear whether this planning will be necessary. Rather than seeking complete regime change, the United States appears content to get rid of Maduro and work with his vice president-turned-president, Delcy Rodríguez — although Trump has made it clear that Rodríguez would have to comply or face “a very high price, probably higher than Maduro’s,” he told the Atlantic.

In the early months of the second Trump administration, Rubio took a more reserved role, allowing the president’s longtime friend Steve Witkoff and his son-in-law Jared Kushner to crisscross the world on their private planes, serving as Trump’s key interlocutors with the Israelis, Russians and Ukrainians.

But as the administration took hold, so did Rubio. In May, he became acting national security adviser, replacing Mike Waltz in the wake of Signalgate, when Waltz accidentally added journalist Jeffrey Goldberg to a government messaging channel on the Signal app on the eve of U.S. strikes against Houthi rebels in Yemen.

With this new position, Rubio gained an office in the White House, allowing him to remain close to the president.

He often joked about wearing many hats in the administration.

But on Saturday, in the presidential residence, he appeared center stage. “Now you have Secretary Rubio, asserting his influence, asserting that of the United States, in the region like we’ve never seen before, certainly not in recent decades,” Bartlett said.

Mark Jones, a researcher at the Baker Institute for Public Policy at Rice University in Houston, Texas, said Rubio’s fingerprints were all over the Venezuela operation.

“Rubio has long been a hawk on Venezuela, and particularly on Cuba,” he said. “And so that fits very well with that.”

Indeed, one possible side effect of Maduro’s capture is the destabilization of Cuba, a country that has long depended on discounted oil from Venezuela, its close ally.

“We already have a Cuba that is experiencing power outages that last dozens of hours a day. The economy is faltering and is on its last legs,” Jones said. “This could be the straw that broke the camel’s back for the Cuban communist regime.”

Rubio hinted at the possibility during a speech at Mar-a-Lago, joking: “If I lived in Havana and I was in government, I would be worried.”

Saturday’s actions constitute a “seismic development for the region,” said Jason Marczak, senior director of the Adrienne Arsht Center for Latin America at the Atlantic Council in Washington, DC.

“This is the first concrete outcome of Trump’s new national security strategy, with a strong focus on the Western Hemisphere.”

Rubio helped draft this document, which calls for hemispheric control.

Unlike Trump’s first national security strategy or even that of his predecessor Joe Biden, the 2025 edition moves away from great power competition with China and Russia to focus instead on spheres of influence.

In the days following Maduro’s capture by the United States, several administration officials, including Trump, made reference to it.

“Under our new national security strategy, American dominance in the Western Hemisphere will never again be questioned,” Trump said Saturday.

This plan is perhaps the most striking example of the influence Rubio has acquired within this administration.

“It was good, wasn’t it? I wrote it myself,” he joked in response to a question from CBC News during his end-of-year press conference.

But he quickly hesitated. He was simply “involved” in writing it, he said — suggesting, as he often does, that he is simply part of a team whose job is, ultimately, to carry out the president’s vision.