Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

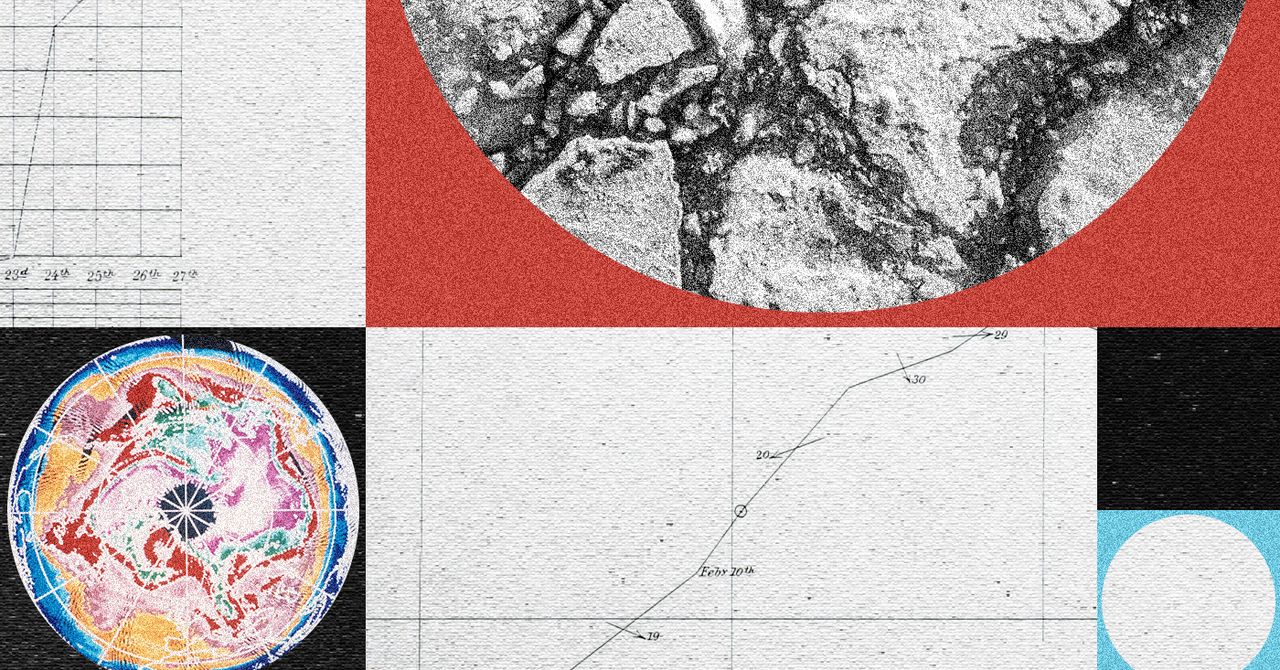

Since 2018, a A group of researchers from around the world have calculated the amount of heat available in the world. oceans are absorbent every year. In 2025, their measurements broke records again, making it the eighth consecutive year that the planet’s oceans have absorbed more heat than in previous years.

The study, published Friday in the journal Advances in Atmospheric Science, finds that the world’s oceans absorbed an additional 23 zettajoules of heat in 2025, the highest figure since modern measurements began in the 1960s. That’s significantly higher than the additional 16 zettajoules they absorbed in 2024. The research is being carried out by a team of more than 50 scientists in the United States, Europe and in China.

A joule is a common way to measure energy. A single joule is a relatively small unit of measurement: almost enough to power a small light bulb for one second, or slightly heat a gram of water. But a zettajoule is one sextillion joules; numerically, the 23 zettajoules that the oceans absorbed this year can be written as 23,000,000,000,000,000,000,000.

John Abraham, a professor of thermal sciences at the University of St. Thomas and one of the paper’s authors, says he sometimes struggles to put that number in contexts that laypeople understand. Abraham offers a few options. His favorite is to compare the energy stored in the ocean to the energy of atomic bombs: the 2025 warming, he says, is the energy equivalent of 12 Hiroshima bombs exploding in the ocean. (Other calculations he has done include equating this figure to the energy it would take to boil 2 billion Olympic-sized swimming pools, or more than 200 times the electricity consumption of everyone on the planet.)

“Last year was a crazy, crazy warming year – that’s the technical term,” Abraham joked to me. “The peer-reviewed scientific term is ‘crazy.’ »

The oceans are the world’s largest heat sink, absorbing more than 90 percent of the excess heat trapped in the atmosphere. Although some of the excess heat warms the ocean surface, it also moves slowly to deeper parts of the ocean, aided by circulation and currents.

Global temperature calculations, like those used to determine the hottest years on record, typically only capture measurements taken at the ocean surface. (The study finds that global sea surface temperatures in 2025 were slightly lower than in 2024, which is recorded as the hottest year since the beginning of modern records. Certain weather phenomena, like El Niño events, can also increase sea surface temperatures in certain areas, which can cause the entire ocean to absorb slightly less heat in a given year. This helps explain why there was such an increase in ocean heat content between 2025, which gave rise to a weak La Niña at the end of the year, and 2024, which came at the end of a strong El Niño year.) Although sea surface temperatures have increased since the Industrial Revolution, thanks to our use of fossil fuels, these measurements do not give a complete picture of how climate change is affecting the oceans.

“If the entire world were covered in a shallow ocean only a few feet deep, it would warm at more or less the same rate as the earth,” says Zeke Hausfather, a research scientist at Berkeley Earth and co-author of the study. “But because much of this heat sinks into the depths of the ocean, we see a generally slower warming of sea surface temperatures. [than those on land].”