Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

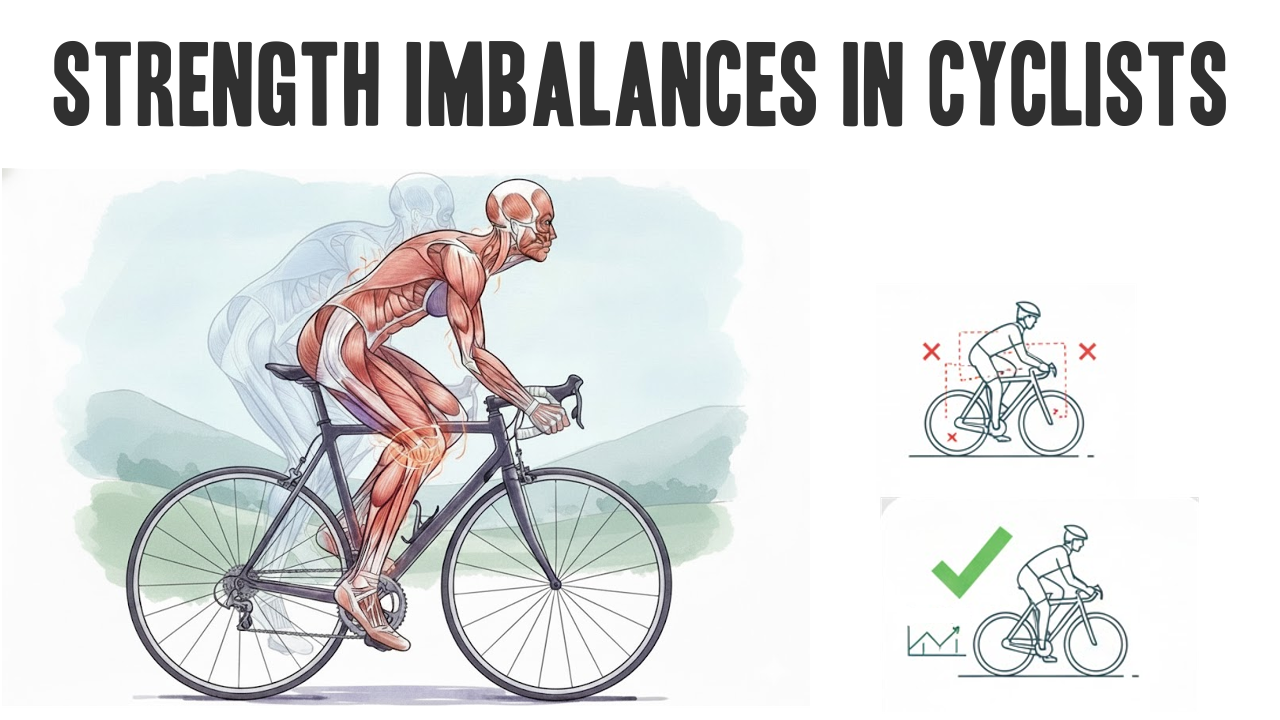

Cycling builds impressive endurance and leg strength, but repetitive pedaling can lead to uneven development. Some muscles adapt quickly while others lag, affecting posture, force application and overall riding comfort. When these imbalances become more pronounced over time, they influence both performance and long-term resilience.

Cyclists of all skill levels are familiar with this pattern because riding relies on a limited range of motion. Repeatedly spending hours sitting with your hips flexed and your torso leaning forward strengthens the same muscular actions. A targeted approach to strength and mobility helps restore balance so cyclists can train harder, feel more stable, and reduce the risk of physical setbacks.

Cycling relies on a predictable sequence of movements. Each pedal stroke lifts and extends the knee, guiding the foot through a small arc. This narrow range develops a strong quadsbut the muscles in the back of the hips and legs don’t always receive the same level of engagement. When one domain does more work than its counterparts, imbalances ensue.

The quadriceps bear much of the workload during each descent. If the glutes and hamstrings can’t share the effort, the knees often take on more force than they’re designed for, affecting comfort and efficiency. Over time, this tendency can influence how the hips track and how power is transferred through the lower body.

Prolonged time sitting also encourages tightening of the hip flexors. Once these muscles shorten, they limit hip extension and limit the glutes’ ability to contribute to each movement. This change increases the use of the lower back and quadriceps. Cyclists may notice discomfort in these areas long before recognizing the underlying cause.

Upper body imbalances appear for similar reasons. Rounded forward head and shoulders often develop during long rides, especially when the spine does not move through a full range of motion during the week. Tightness in the chest and weakness in the upper back can influence breathing mechanics and add tension to the neck.

These changes occur slowly and often without visible signs at first. As training volume increases, imbalances affect both running quality and the body’s ability to handle repetitive stress.

When certain muscles dominate the workload, the joints and connective tissues compensate. This often manifests as tight hips, irritated knees, or lower back fatigue during or after rides. Weak stabilizers also limit the body’s ability to maintain alignment under load, affecting comfort and consistency.

Unexpected movements can create additional challenges. If the core or hips cannot control sudden changes in force, the body has a harder time absorbing the impact or correcting its position. This contributes to overuse problems and can influence how the body responds during more serious events.

Cyclists also face the risk of falls or collisions. Understand the patterns observed in common injuries in bicycle accidents gives context to the types of trauma that can occur during these incidents. Imbalances don’t cause falls, but strong supporting muscles help the body handle sudden forces more effectively. When the hips, core, and upper back work together, the body tends to respond with more stability and control.

Awareness of these risks encourages runners to train in a way that promotes balanced strength throughout the body.

Strength training gives cyclists the tools to correct uneven development and improve support around the joints that absorb the most stress. A balanced program targets the hips, legs, core and upper back to build more stable mechanics on the bike.

Posterior chain exercises such as hip hinges, Romanian deadlifts, and glute bridges develop the muscles that share the load with the quadriceps. This helps reduce knee strain and improves the way power moves with each stroke. When these muscles work consistently, cyclists often notice smoother transitions and less fatigue in the lower back.

Hip stability plays a central role in the alignment of the knee and pelvis. Single-leg squats, step-downs, and banded hip exercises help the body stay in control when pressure increases. Strong stabilizers guide the knees onto more stable paths and resist unwanted movement.

Core training supports posture and helps manage repetitive loads. Planks, anti-rotation exercises, and core endurance exercises strengthen the spine and reduce unnecessary movement. Research into core stability and athletic mechanics highlights the positive effects of consistent core development, as explained in the review of core stability training for injury prevention.

Upper back strengthening work, including rows and scapular control exercises, promotes better breathing and reduces tension in the neck and shoulders. These exercises help counteract the rounded posture that often develops during long rides.

Strength work prepares the body for cycling by building balanced support rather than relying on a single dominant pattern.

Mobility training restores the movement that repetitive pedaling can limit. When joints move freely, muscles share the workload more evenly and maintain better control throughout each ride.

Hip mobility helps engage the glutes and reduces strain on the quads and lower back. Controlled rotations, active stretches and dynamic movements help open the front of the hips and promote long-term alignment.

Thoracic mobility influences posture and breathing. Simple extension exercises and rotation patterns help the upper back maintain a more neutral position, which reduces excess tension in the shoulders.

Ankle mobility affects how smoothly force travels up the chain. Limited ankle reach can alter knee tracking and reduce energy efficiency. Gentle dorsiflexion work can improve this pattern and contribute to a more controlled pedal stroke.

These mobility practices complement strength training by promoting smoother, more efficient movements.

Physical conditioning helps cyclists strengthen balanced movements and build the endurance needed for long rides. It also teaches the body to coordinate muscle groups to promote better alignment.

Low-intensity cadence intervals promote even force distribution across both legs and strengthen underused muscles. Single-leg exercises performed at a controlled pace highlight areas that require more stability and coordination.

Neuromuscular conditioning sharpens the body’s ability to adapt quickly. Balance and core control exercises help maintain alignment when terrain changes or fatigue builds. These movements also reinforce the strength work done at the start of the week.

Mobility-based conditioning combines flexibility and control. This approach helps reduce stiffness from repetitive bending and promotes smoother hip movement. Riders can add hip circles to their routine to improve hip control and alleviate tension that builds up during long sessions.

These conditioning practices contribute to a more balanced and resilient cycling model.

A simple weekly structure helps integrate strength, mobility and conditioning into a busy training schedule. This plan allows for steady progress while still leaving room for regular runs.

Day 1: Focus on strength

Posterior chain work, hip stability exercises and core endurance exercises.

Day 2: Mobility and conditioning of light

Hip and chest mobility combined with easy cadence work.

Day 3: Core Strength and Integration

Lower body strength, single leg exercises and core control exercises.

Day 4: Focus on conditioning

Cadence intervals, single leg efforts and neuromuscular balance work.

Day 5: Recovery and mobility

Gentle stretches, controlled movements and stress-free mobility exercises.

This routine encourages regular adaptation without overloading the body.

Strength imbalances develop naturally in cyclists, but they can be corrected through deliberate training. When riders support the hips, core and upper body with targeted strength and mobility work, they create a more stable and efficient foundation for every ride. A consistent approach leads to more power, better alignment and fewer setbacks during long hours on the bike.