Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

The weakest job market since 2011 is increasingly being framed not as a problem, but as the new normal — a market where growth roars and jobs barely move, leaving a generation wondering, “Dude, where’s my job?”

Bank of America Research’s “Situation Room” note warned in mid-December that markets were pricing in a robust 2026, even if hiring stagnates and unemployment rises, and reiterated a now a cult classic stoner comedy, 25 years old with Ashton Kutcher and Seann William Scott to make his point.

In other words, the entry-level worker would be forgiven for having the same feelings about his job search that Kutcher and Scott have about their stolen wheels. (The screenwriter feels the same way about the show business job market, developer The Hollywood Reporter a few weeks ago that he quit to become a therapist.)

“The job market has been weak this year,” wrote Yuri Seliger and Sohyun Marie Lee of BofA, commenting on the article. double payroll report showing weak job growth in October and November. “The lack of recovery in the job market and the slowdown in the American economy constitute major risks to monitor for 2026.”

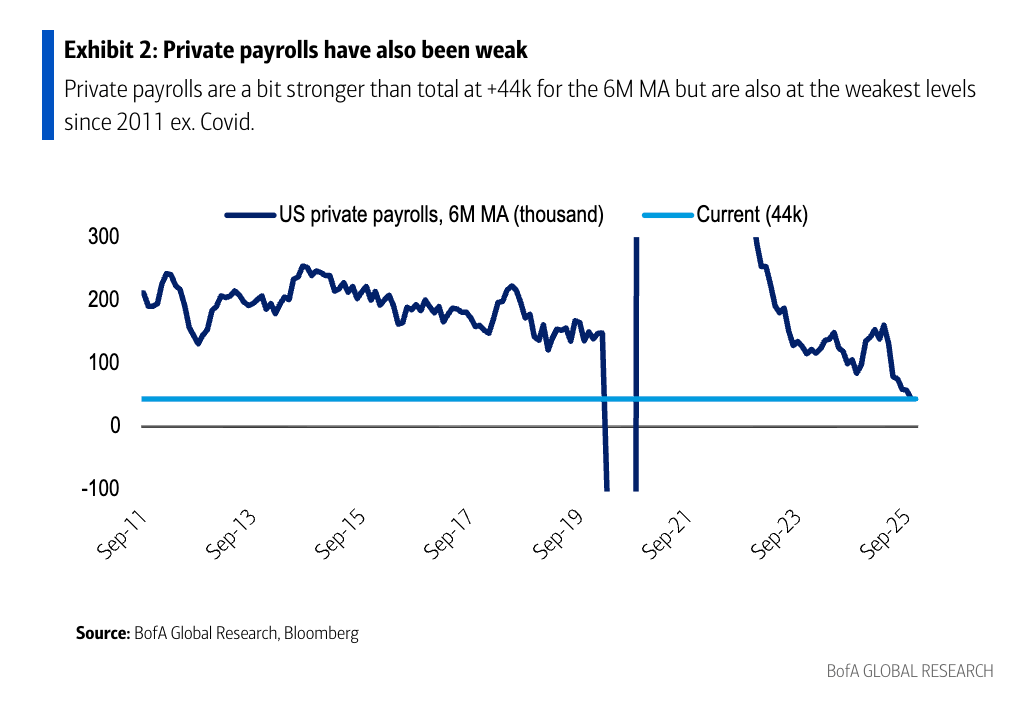

Seliger and Lee reported what they call the weakest U.S. labor market since at least 2011 (with the notable exception of the wave of mass layoffs due to Covid), with an average monthly payroll of just 17,000 over the past six months — by far the slowest pace of job creation since the global financial crisis. Private sector payrolls are only slightly stronger, at 44,000 on a six-month average basis, remaining at their lowest level in more than a decade, while broader underemployment of under-6s climbed to 8.7% and job openings per unemployed person fell to 1.0, both the lowest since 2017.

Yet the Situation Room team also noted that credit spreads remain near cyclical lows and stocks near record highs, indicating that investors are still betting on a strong expansion in 2026. “A strong U.S. economy is likely not consistent with no job growth,” they caution, warning that the lack of a labor market recovery is now one of the main risks of this bullish market narrative. The surprisingly strong GDP figure for the third quarter, revealed after the BofA memo was written, added fuel to the fire of this argument.

The overall growth figure was eye-catching: in the third quarter, US GDP grew at an annual rate of 4.3%fueled by a surge in consumer spending and a $166 billion jump in corporate profits. But real disposable income remained flat – literally 0% growth – meaning that households did not gain purchasing power and instead resorted to savings, credit and cost-cutting to continue spending, especially on unavoidable areas like health care and child care.

KPMG Diane Swonk, chief economist described this previously at Fortune as a mature K-shaped economy, where wealthy households benefit from rising stock markets, high home values and AI-boosted corporate profits, while low- and middle-income families are crushed by affordability pressures and stagnant real incomes.

Companies, she argued, have learned to grow without hiring, leveraging more output from smaller teams rather than increasing payroll to meet demand — a trend that aligns with BofA’s evidence that payroll gains are historically small in an otherwise strong macroeconomic backdrop. “Our view is that most of the productivity gains we’re seeing now are really just the result of companies being reluctant to hire and doing more with less,” Swonk said. Fortune. “Not necessarily AI yet.”

His analysis matched what BofA Savita Subramanian said Fortune in August, on a “step change” in worker productivity, with companies replacing people with processes. Businesses have learned to “do more with fewer people” after post-pandemic inflation, and she predicts this will be positive for stocks: “A process is almost free and it is repeatable for eternity. »

Darker still, economists at Goldman Sachs have warned of the prospect of “jobless growth”. In an October noteGoldman economists David Mericle and Pierfrancesco Mei found that outside of the healthcare sector, net job creation has become low, zero, or negative in many sectors, even as output continues to rise, with executives increasingly focusing on using AI to reduce labor costs — a “potentially lasting headwind to labor demand.”

They argued that the modest job gains alongside robust GDP seen recently are “likely to be normal to some extent in the years ahead”, with most growth coming from productivity – particularly AI – while demographic aging and falling immigration limit contributions to labor supply.

Apollo’s Torsten Slok pointed out in a December note that demographic change is now becoming visible: The number of families with children under 18 peaked at around 37 million in 2007 and declined to around 33 million in 2024, reflecting lower birth rates and an aging population, despite continued overall population growth.

BofA and Goldman aren’t predicting mass unemployment, but neither sees an easy way to return to the old model that strong GDP reliably meant plentiful new jobs. Still, Goldman predicts a bigger upheaval for the economy: “History also suggests that the full labor market consequences of AI may not become apparent until a recession hits,” Mericle and Mei wrote in October.

Meanwhile, the job market of the mid-2020s may remain defined less by layoffs than by the scarcity of opportunities – especially for Generation Z – an era of hugs at work at the top and job search in vain at the bottom. In light of the GDP numbers and the prospect of jobless growth on the horizon, BofA’s glib, retro question may well become even more pressing in the new year: Where are the jobs?