Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Jeremy BowenInternational publisher

Getty Images

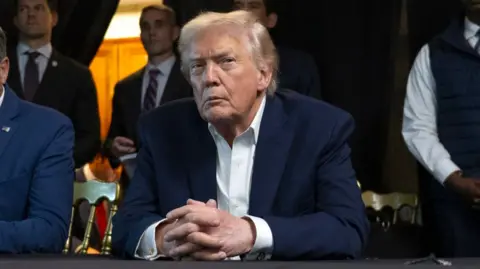

Getty ImagesJust hours after Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro was forced out of his palace, his job and his country by US special forces, Donald Trump was still marveling at what it was like to watch the raid live from his Mar-a-Lago mansion.

He shared his feelings with Fox News.

“If you could see the speed, the violence, they call it that… It was incredible, incredible work by these people. No one else could do something like that.”

The American president wants and needs quick victories. Before taking office for the second time, he boasted that ending the war between Russia and Ukraine would be just a day’s work.

Venezuela, as presented in Trump’s statements, is the quick and decisive victory he dreamed of.

Maduro is in a Brooklyn jail cell, the US will “run” Venezuela – and he has announced that the Chavista regime, now with a new president, will hand over millions of barrels of oil and that he will control how the profits are spent. All this, at least so far, without loss of American life and without the long occupation that had such catastrophic consequences after the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

For now, Trump and his advisers are ignoring, at least publicly, the complexities of Venezuela. It is a country bigger than Germany, still ruled by a factional regime that has integrated corruption and repression into Venezuelan politics.

Instead, Trump is enjoying a geopolitical sugar rush. Judging by their statements when they flanked him at Mar-a-Lago, so are U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio and Secretary of War Pete Hegseth.

Since then, they have repeated that Trump was a president who does what he says he does.

He made it clear to Colombia, Mexico, Cuba, Greenland – and Denmark – that they should be concerned about where his appetite would take him next.

Trump likes nicknames. He still calls his predecessor Sleepy Joe Biden.

He is now trying to give a new name to the Monroe Doctrine, which has been the bedrock of US policy in Latin America for two centuries.

Trump renamed it, of course, in his honor: the Donroe Doctrine.

James Monroe, the fifth president of the United States, unveiled the original in December 1823. It declared the Western Hemisphere to be America’s sphere of interest – and warned European powers not to interfere or establish new colonies.

The Donroe Doctrine puts Monroe’s 200-year-old message on steroids.

“The Monroe Doctrine is a big deal, but we’re way past it,” Trump said at Mar-a-Lago as Maduro, blindfolded and shackled, was on his way to prison.

“Under our new national security strategy, American dominance in the Western Hemisphere will never again be challenged.”

Reuters

ReutersAny rival or potential threat, especially China, must stay out of Latin America. It is unclear what the status of the massive investments that China has already made in the region are.

Donroe also extends the huge area the United States calls its “backyard” north to Greenland.

The 2026 equivalent of Monroe’s copperplate writing is a photo of a scowling and brooding Trump, posted by the US State Department on social media. The accompanying words read: “this is OUR hemisphere – and President Trump will not allow our security to be threatened.”

That means using U.S. military and economic power to coerce countries and leaders who stray from course — and to take their resources if necessary. As Trump warned of another possible target, the president of Colombia, they need to watch their butts.

Greenland is in the crosshairs of the United States, not only because of its strategic importance in the Arctic, but also because it has rich mineral resources that are becoming accessible as climate change melts the ice caps. Greenland’s rare earths and Venezuela’s heavy crude oil are both considered strategic assets of the United States.

Unlike other interventionist American presidents, Trump does not hide his actions under the legitimacy, however fallacious, of international law or the pursuit of democracy. The only legitimacy he needs comes from his belief in the force of his own will, backed by the raw power of the United States.

From Monroe to Donroe, foreign policy doctrines matter to American presidents. They shape their actions and their legacy.

In July, the United States will celebrate its 250th anniversary. In 1796, its first president, George Washington, announced that he would not seek a third term, in a farewell speech that still resonates today.

Washington has issued a series of warnings to the United States and the world.

Temporary wartime alliances might be necessary, but otherwise the United States should avoid permanent alliances with foreign countries. This is how the tradition of isolationism was born.

At home, he warned citizens to be wary of extreme partisanship. Division, he said, posed a danger to the young American republic.

The Senate conducts a public rereading of Washington’s farewell speech every year, a ritual that does not transgress the hyper-partisan and polarized politics of the United States.

Washington’s warning about the dangers of tangled alliances was heeded for 150 years. After World War I, the United States left Europe and returned to isolationism.

But World War II made the United States a world power. And this is where another doctrine comes in, much more significant for the way Europeans have lived – until Trump.

By 1947, the Cold War with the Soviet Union had turned glacial. The United Kingdom, left bankrupt by the war, told the United States that it could no longer finance the Greek government’s fight against the communists.

Then-President Harry Truman’s response was to commit the United States to supporting, in his words, “free people who resist attempts at subjugation by armed minorities or by external pressure.” He spoke of threats from the Soviet Union or local communists.

It was the Truman Doctrine. It led to the Marshall Plan which rebuilt Europe, followed in 1949 by the creation of NATO. In the United States, Atlanticists, such as Harry Truman and George Kennan – the diplomat who came up with the idea of containing the Soviet Union – believed that these commitments were in America’s interest.

There is a direct link between the Truman Doctrine and Joe Biden’s decision to fund Ukraine’s war effort.

In many ways, the Truman Doctrine created a relationship with Europe that Trump is dismantling. It was a sharp break with the past. Truman ignored Washington’s warning about permanent and entangling alliances.

Today, Trump breaks with Truman’s legacy. If he carries out his threat to take possession of Greenland, Denmark’s sovereign territory, he could destroy what remains of the transatlantic alliance.

Maga ideologue and powerful Trump advisor Stephen Miller summed it up earlier this week on CNN. The United States, he said, operates in a real world that “is ruled by force, that is ruled by force, that is ruled by might…these have been the iron laws of the world since the dawn of time.”

No American president would deny the need for strength and power. But from Franklin D. Roosevelt, through Truman and all their successors to Trump, the men in the Oval Office believed that the best way to be powerful was to lead an alliance, and that meant give and take.

They supported the new UN and the desire to establish rules to regulate the behavior of states. The United States, of course, has ignored and violated international law on numerous occasions – thereby helping to hollow out the idea of a rules-based international order.

But Trump’s predecessors did not attempt to dismiss the idea that the international system needed regulation, however imperfect and incomplete it might be.

This is due to the catastrophic consequences of the rule of the strongest in the first half of the 20th century: two world wars and millions of deaths.

But the combination of Trump’s “America First” ideology and his businessman’s acquisitive, deal-making instincts has led him to believe that America’s allies must pay for the privilege of his favor. Friendship seems like too strong a word. America’s interests, in the narrow definition articulated by the president, require that it remain at the top by acting alone.

Trump often changes his mind. But one constant seems to be his belief that the United States can use its power with impunity. He says it’s the way to make America great again.

The risk is that if Trump sticks to his course, he will return the world to what it was in the age of empires a century or more ago – a world where great powers, with their spheres of influence, sought to impose their will, and powerful authoritarian nationalists led their peoples into disaster.