Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

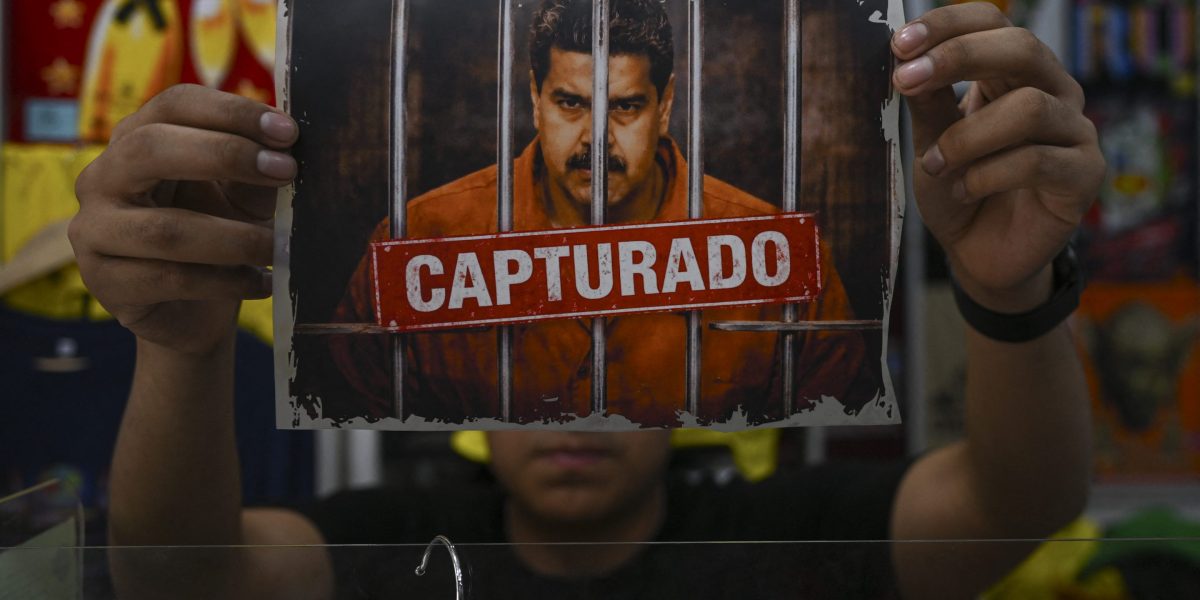

The U.S. mission to seize Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro has brought the concept of regime change back into everyday conversations. “Regime Change in America’s Backyard” said the New Yorker in an article that characterizes the response to the January 3 operation that saw Maduro swap a compound in Caracas for a prison in Brooklyn.

Commentators and politicians have used the term as shorthand for Maduro and ending the crisis in Venezuela, as if the two were essentially the same thing. But that’s not the case.

In fact, to a specialist in international relations like meUsing the term “regime change” to explain what just happened in Venezuela confuses the term rather than clarifying it. I’ll explain to you.

Regime change, as it has been practiced and discussed in international politics, refers to something far more ambitious and far more consequential than the removal of a single leader. It is an attempt by an outside power to transform the way another country is governed, not just to change who governs it.

Of course, this does not mean that regime change in Venezuela is not yet possible. However, Maduro being replaced by his deputyformer Vice President Delcy Rodríguez, has not yet reached that bar – although, as US President Donald Trump has suggested, she will under pressure to toe the Washington line.

Understanding this distinction is essential to grasp the challenges facing Venezuela in its transition to a post-Maduro world. necessarily a far removed from the Chavista ideology that Maduro inherited from his predecessor, Hugo Chavez.

Change of dietas understood by most foreign policy analysts, refers to efforts by external actors to impose a profound transformation in the system of government of another state. The goal is to reshape who holds authority and how power is exercised by changing the structure and institutions of political power, rather than a government’s policies or even its personnel.

When understood in this way, the history of the term becomes clearer.

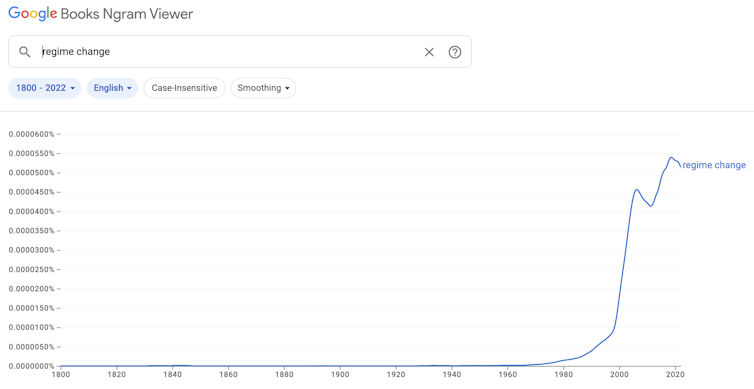

The concept of “regime change” was widely used after the Cold War as a way to describe an externally imposed political transformation without relying on older, more direct terms.

Military and political leaders in earlier eras tended to speak openly about overthrowing, deposing, invading, or interfering in the internal affairs of another state.

In contrast, the more recent term “regime change” seems technical and sober. It suggested planning and management rather than domination, mitigating the reality that this was the deliberate dismantling of another country’s political order.

This choice of language mattered. Describing the overthrow of governments as “regime change” reduced the moral and legal weight associated with coercive intervention. It also assumed that political systems could be taken apart and rebuilt through expertise and design. The term implied that once an existing order was removed, another more acceptable one would take its place and that this transition could be externally guided. During the 1990s and early 2000s, this hypothesis integrated in the thinking of the American foreign policy establishment. Regime change came to be associated with ambitious efforts to replace hostile governments with fundamentally different systems of government. Iraq has become the most important test of this idea. American intervention in 2003 succeeded in overthrowing Saddam Hussein’s governmentbut it also revealed the limits of externally driven transformation. Along with Hussein, senior members of his long-ruling Baath Party were barred from participating in the new government – this was true regime change. The collapse of the existing order in Iraq following the US-led invasion, however, did not result in a stable successor. Instead, it produced a violent struggle for power that outside powers were unable to control. This experience changed the way the term was understood. The term regime change has not disappeared from political debate, but its meaning has changed. It has become a label linked to concerns about the overreach and risks of assuming that foreign powers can reorganize political systems. In this usage, regime change no longer promised control or resolution. It functioned as a warning from experience. Both meanings are now visible in discussions about Venezuela. Certain audiences invoke a change of regime to signal a determination and desire to break an entrenched system that appears resistant to reform. Others hear the same term and think about past cases where the collapse of a regime has produced fragmentation and prolonged instability. The importance given to this concept depends on who uses it and the political objective they pursue. This distinction is important because regime change driven by external factors does not end with the fall of a government or the removal of a dictator. This triggers a competition over how power will be reorganized once existing institutions are dismantled. This article is part of a series explaining the terms of foreign policy commonly used but rarely explained. Andrew Lathamprofessor of political science, Macalester College This article is republished from The conversation under Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

And then came Iraq

A nice distinction

![]()