Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

After half a century immersed in the world of trade, customs broker Amy Magnus thought she had seen it all, overcoming mountains of regulations and all manner of logistical hurdles to import everything from lumber and bananas to circus animals and Egyptian mummies.

Then came 2025.

Tariffs were imposed in a way she had never seen. The new rules made her wonder what they really meant. Federal workers, always a reliable support, became increasingly elusive.

“2025 changed the trading system,” says Magnus. “Before, it wasn’t perfect, but it was a system that worked. Today, it’s much more chaotic and unsettling.”

Once hidden cogs in the international trade machine, customs brokers are enjoying a rare spotlight as President Donald Trump reinvents America’s trade ties with the world. If this breathtaking year of tariffs amounts to a trade war, customs brokers are on the front lines.

Few Americans have been so comprehensively exposed to all fluctuation of trade policy as a customs broker. They were there from the first days of Trump’s second term, when tariffs were announced on Canada and Mexico, and two days later, when those same levies were suspended. They were present in all the rules on steel and seafood imports, on cars and copper, on polysilicon and pharmaceuticals, and so on. For every rate, for every exclusion, for every order, brokers had to translate the policy into reality, line by line and code by code, during a year when it seemed like every passing week brought change.

“We were used to decades of a certain way of processing, and from January until now, that universe has been kind of turned upside down,” says Al Raffa, a customs broker in Elizabeth, New Jersey, who helps move containers of goods to the United States, filled to the brim with everything from rounds of brie to boxes of chocolate.

Each arrival of imported products into the country requires reporting to U.S. Customs and Border Protection and often to other agencies. Importers often turn to brokers to handle regulatory paperwork, and with a series of new trade rules imposed by the Trump administration, they have seen their demand increase along with their workload.

Many shipments that entered duty-free are now subject to tariffs. Other imports subject to minimal levies that can cost a company a few hundred dollars have seen their bills climb into the thousands of dollars. For Raffa and his team, the ever-longer price list means that a given product could be subject to taxes under several distinct tariff lines.

“This line of cheese that previously had just one tariff, could now have two, three, in some cases five tariff numbers,” says Raffa, 53, who has worked in the trade since his teens and wears a button reading “Make Trading Boring Again.”

Government regulations have always been a reality for brokers and the very reason for their existence. However, when large volumes of business rules have been amended in the past, they have typically been published well in advance of their effective date, with comment and review periods, with each word of policy written with the intent of projecting clarity and definition.

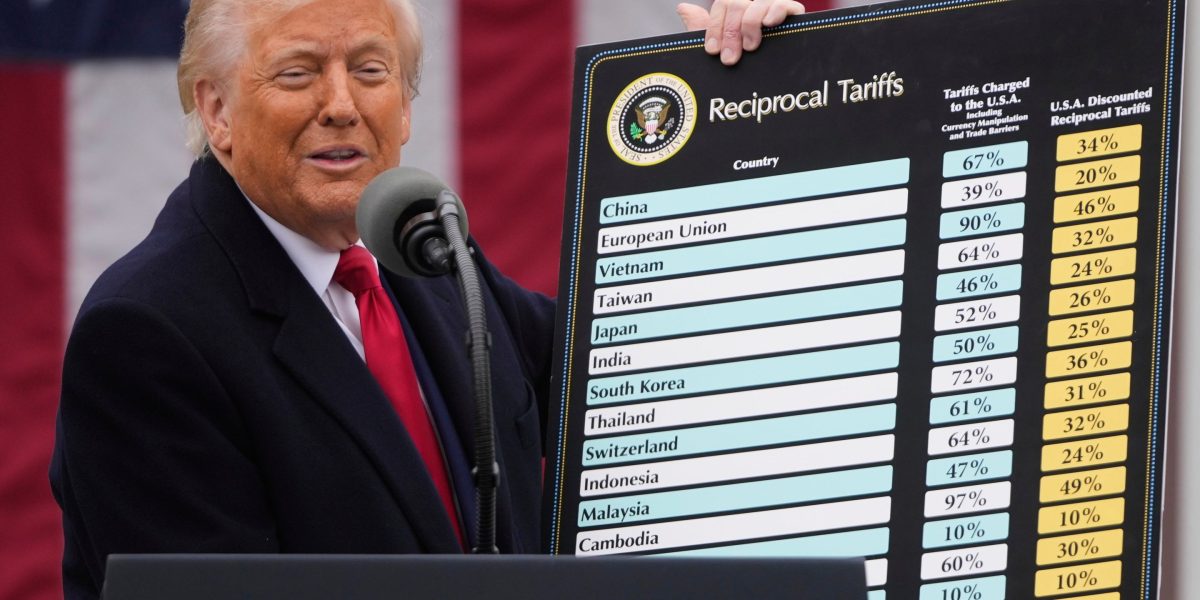

With Trump, word of major change in business rules could appear in a Truth Social article or in an oversized painting held by the president during a Rose Garden appearance.

“You would be remiss not to check the White House website daily, several times a day, just to see what executive order is going to be announced,” Raffa says.

Each announcement pushes brokerages to analyze the rules, update their systems to reflect them and alert their clients who might have shipments on the way and for whom any change in rates could have a major impact on their bottom line.

JD Gonzalez, a third-generation customs broker in Laredo, Texas, and president of the National Customs Brokers and Forwarders Association of America, says the volume and speed of change have been challenging enough. But the wording of the White House orders has often left more questions unanswered than brokers are accustomed to.

“The order is sometimes vague, the advice provided is sometimes unclear and we are trying to make a decision,” says Gonzalez, 62.

Gonzalez lists the 10-digit tariff codes for alcohol and doors and recites the complex web of rules that determine duties on a chair with a steel frame produced in the United States but processed in Mexico. As brokers’ jobs have become more difficult, he says some of their companies have started charging clients more for their services because each item they are responsible for tracking on a bill of lading takes longer.

“You double the time,” he said.

Brokers can’t help but see the imprints of their work everywhere they go. Gonzalez looks at the label of a T-shirt and thinks about what a broker did to bring it into the country. Magnus sees Belgian chocolate or Chinese silk and is impressed that, despite everything that might have stopped something from landing on a store shelf, it still arrived. Raffa walks through the supermarket, picks up a box of artichoke hearts, and thinks about all the possible regulations that could apply to ensure its importation into the country.

It was heartening for brokers, who existed in the gray arcana of hidden bureaucracy, invisible to most Americans, to now gain a little more recognition.

“It was perhaps taken for granted that this wonderful piece of gourmet cheese hit the shelves, or that Gucci bag,” says Raffa. “Until this year, people had no idea what I was doing.”

Magnus, about 70 years old and based in Marco Island, Fla., spent 18 years in U.S. Customs before starting at a brokerage firm in 1992. She found solace in the precision of the rules governing every import she blazed a trail for, from crude oil to diamonds.

“We don’t like to have doubt, we don’t like to leave anything up to interpretation,” she says. “When we’re struggling ourselves, trying to interpret and understand the meaning of some of these things, it’s a very troubling place to be.”

It wasn’t just orders from the White House that complicated his job.

THE Ministry of Government Effectiveness Billionaire Elon Musk’s cost-cutting campaign has led to layoffs and retirements of trusted officials to whom brokers turn for guidance. A shutdown slowed operations at ports. And fear of being out of step with the administration pushes some federal employees to be cautious in decoding trade orders, making it sometimes difficult to get answers about interpreting tariff rules.

Magnus was disconcerted by measures that seemed at odds with everything she knew about trade policy. Canada as an adversary? Switzerland subject to customs duties of 39%? It challenged how she had come to view cargo choreography and what it says about the world.

“It’s like an incredible ballet to be able to trade with all these countries around the world,” she says. “In my mind, I always thought that as long as we traded and were friendly with each other, we reduced the risk of war and killed each other. »

Work has been so intense this year that Magnus hasn’t managed to take a vacation. Weekends were so often disrupted by Friday afternoon decrees announcing the entry into force or removal of a customs tariff that it became a joke among colleagues.

“It’s Friday afternoon,” she said. “Is everyone watching?”

Hours after Magnus repeats this, the next order from the White House is issued, rolling back a series of tariffs on agricultural products and sending brokers into further turmoil.