Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Katihar, India – Ravjit Singh, a leather clothing trader who lives in Denver, Colorado, has started to feel the effects of US President Donald Trump’s 50% tariffs on Indian goods in recent months.

The 50-year-old from Calcutta, eastern India, told Al Jazeera that rising food prices had wreaked havoc on his household budget, particularly affecting a favorite family snack: fox nuts, commonly known as makhana.

list of 4 elementsend of list

“The monthly budget has increased to $900, compared to $500 before the pandemic, and customs tariffs have made the situation worse,” he said.

A packet of fox nuts weighing about 25 grams (0.9 ounces), which previously cost $2, has doubled in recent months to $4, alongside rising prices of other staples, such as lentils and basmati rice, he added.

Fox nuts are the burst kernels of water lily seeds and are found in tropical and subtropical regions of South and East Asia, with a considerable presence in India, China, Nepal and Japan. Packed with protein, calcium, antioxidants and vitamins, nuts have quickly gained a reputation as important immunity boosters.

But they were not immune to the effects of the customs duties imposed by Trump: the American president first imposed a 25% levy on Indian products, then doubled this amount. at 50 percent due to Indian imports of Russian oil, which he claimed were helping fuel Russia’s war against Ukraine. The tariffs hit companies in several sectors in India for which the United States was a major export market, including those engaged in business. shrimp, diamonds and textiles.

Fox nut exporters have seen U.S. sales fall by as much as 40 percent.

Yet amid the crisis, some also see a glimmer of hope: Indian fox nuts are finding new alternative markets and a growing appetite for this superfood in India.

In India, fox nuts are grown in low-lying areas, particularly in the eastern state of Bihar, and provide a source of income for around 150,000 farmers. The country dominates 90 percent of global production.

The state produces 120,000 tonnes of seeds and 40,000 tonnes of popped fox nuts annually from 40,000 hectares (99,000 acres) of land.

Cultivation is done in shallow agricultural fields with a depth of approximately 1.3 to 1.8 meters (4 to 6 feet). It’s inexpensive because new plants germinate easily from older seeds.

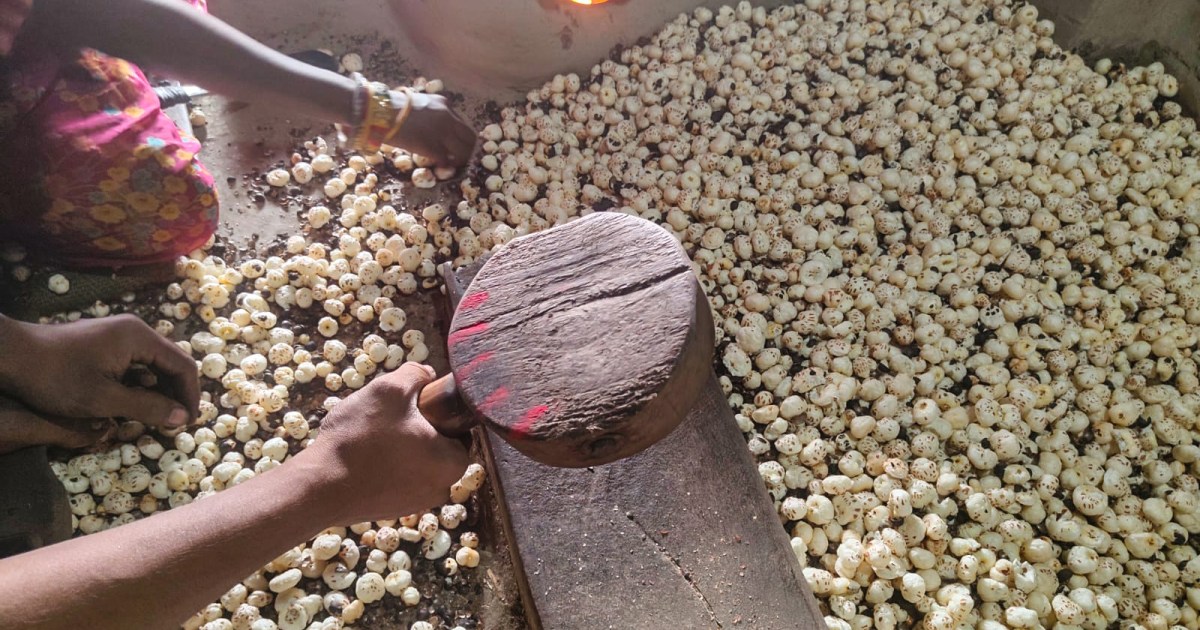

The harvest season begins in mid-July and continues until the end of November, during which workers sweep the entire body of water collected from the fields for seeds with traditional tools like horn-shaped split bamboos and nets, depending on the size of the seeds.

The collected seeds are first dried in the sun, then heated in a clay or iron pan to make the outer shells brittle. The seeds are finally pounded to release the puff of whiter edible makhana, which is roasted again for a final crunch.

In 2024-2025, India exported around 800 metric tonnes of fox nuts to countries like Germany, China, the United States and the Middle East. But the United States – where 50 percent of India’s exported fox nuts go – dominates the market, said Satyajit Singh, whose company, Shakti Sudha Agro Ventures, controls half of India’s total health food exports.

The total turnover of the industry – including the domestic market – is around 3.6 billion rupees ($40 million), Singh told Al Jazeera.

“But the sector offers huge opportunities, as it is still in its infancy and limited to [the] Indian diaspora in [the] international market, and we need to make it more known, both domestically and abroad,” he added.

He is already seeing demand from new markets, such as Spain and South Africa, driven by the Indian diaspora and awareness of the health benefits of fox nuts, he said.

Ketan Bengani, 28, a Kolkata-based fox nut exporter, told Al Jazeera that domestic demand for fox nuts has also doubled every year since the COVID-19 pandemic, when people became aware of the health benefits of these nuts.

Its exports to the United States, of about 46 metric tons, fell 40 percent due to tariffs. But he’s not too worried and hopes to offset that with growing demand in India, he said.

In fact, the high demand has attracted several budding entrepreneurs.

Among them is Md Gulfaraz, 27, a fox nut producer and exporter based in Charkhi village in Purnea district of Bihar.

Gulfaraz told Al Jazeera that the company’s sales increased from 5.4 million rupees ($60,000) in 2019 to 45 million rupees ($500,000) in the financial year ending March 2025, thanks to increased domestic demand.

Makhanas, as fox nuts are popularly known in India, were historically common in Indian cuisines, but like many traditional foods, they have lost out to the slick marketing campaigns, branding and flavors of Western and more modern Indian snacks.

The pandemic served as a blessing in disguise, bringing fox nuts back into favor due to their immunity benefits. Now, makhanas line the shelves of Indian supermarkets, with flavors ranging from peri peri to tangy tomato, cheese to onion and cream.

Sujay Verma, 43, a software engineer in Kolkata who is originally from Bihar and grew up eating fox nuts, told Al Jazeera that he gives his two daughters a plate every day for breakfast.

“We used to rush after packaged food items which were expensive and created a hole in my pocket. But fox nuts are not only cheap but are also good for health,” he said.

The Indian government also saw the commercial potential of fox nuts. Earlier this year, he announced the creation of a makhana board, at an initial outlay of 1 billion rupees ($11 million) to institutionalize the value chain and provide training, technical support, quality regulation and export facilitation to businesses.

The impetus for the Indian government comes from the top: Prime Minister Narendra Modi told a rally earlier this year that he eats fox nuts most of the time and that it is time for India to introduce this superfood to the world.

Farmers and workers are also turning to producing fox nuts from other crops due to higher income.

Anil Kumar, an assistant professor at Bhola Paswan Shastri Agricultural College in Purnia in Bihar, told Al Jazeera that workers who collect the seeds earn about 2,000 rupees ($22) a day for every 50 kg (110 pounds) collected. This is more than double the 700 to 900 rupees ($8 to $10) normally paid to unskilled workers in India.

Fox nut production was limited to 5,000 hectares (12,000 acres) of land in 2010, and farmers were paid 81 rupees ($0.90) per kilogram, he explained. Today, around 40,000 hectares of land are used to grow fox nuts, while farmers receive 450 rupees ($5) per kilo.

“Customs duties will not harm us as demand is growing globally,” said Satyajit of Shakti Sudha Agro Ventures.