Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Warren Buffett’s failure to capitalize on the digital shift in the economy over the past two decades has hurt his otherwise enviable track record as an investor. His blind spot regarding technology didn’t stop at the stock market: this was also reflected in the way he ran Berkshire Hathaway’s operating companies. In many of his wholly owned businesses, Buffett neglected technology upgrades, and Berkshire’s business value suffered.

This is important to understand because the majority of Berkshire Hathaway’s assets are not invested in publicly traded securities, but in operating subsidiaries like Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad, Berkshire Hathaway Energy and Geico. While it’s true that Buffett has invested aggressively in wind energy, it’s largely due to government tax incentives. For the most part, it preferred to exploit its operating subsidiaries for cash rather than reinvesting in them for the digital age. Exhibit A is Geico, which, due to a lack of IT investment, has fallen behind Progressive as the nation’s first for-profit auto insurer.

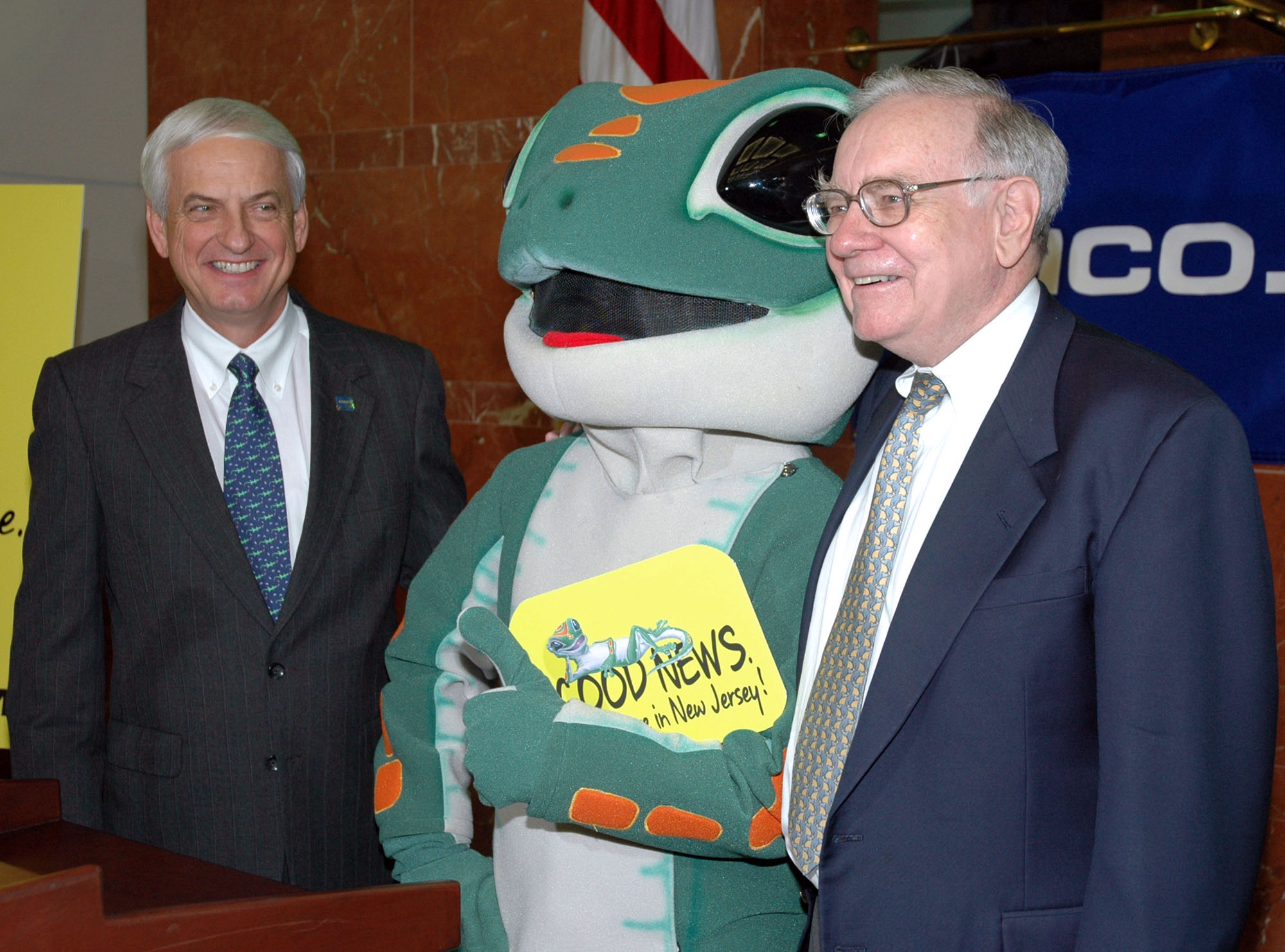

Buffett has called Geico his favorite child, and for good reason. Since its beginnings in the 1930s, the auto insurer has used a direct sales model to keep its operating costs low in the industry. In a commodity sector like insurance, this constitutes a major competitive advantage. In the 1990s, after purchasing all of Geico, Buffett found a second moat when he began to present Geico as a trusted, even beloved, American company. The gecko, the caveman, the camel that celebrated hump day – it was all a marketing masterstroke, directly derived from Buffett’s deep understanding of the brand and mass media industrial complex. The mascots also point out that while Buffett was comfortable with investing in marketing, he was deeply uncomfortable with investing in technology and therefore did not understand investing in technology.

When Buffett took control of Geico in 1996, he increased its marketing budget eightfold. This wiped out almost all of Geico’s profits from a GAAP accounting perspective, but Buffett was convinced that increasing ad spending today would lead to more profitable customers tomorrow. And so it did: under Buffett’s leadership, Geico’s market share grew from less than 3% in 1996 to 12% in 2020, and it went from the 7th largest auto insurer to the 2nd largest auto insurer, behind State Farm.

So far, so good, but while Geico was investing in marketing, rival Progressive was investing in technology. Founded only a year after Geico, Progressive began upgrading its computer systems beginning in the late 1970s. In the 1980s, it bought its agents computers and sent them floppy disks so they could better match price to risk. In 1996, Progressive became the first auto insurer to allow consumers to buy insurance online, and it has continually streamlined its back-end systems so it can accurately deliver new business. Today, Progressive boasts that it has tens of billions of price points and that its technology stack allows it to adjust its prices much more quickly than its competitors, almost once per business day. “We’re a technology company that sells insurance” is one of Progressive’s internal mantras.

The company’s technology investment was based on a vision perhaps even more astute than Buffett’s marketing vision. Through its agent-free, commission-free model, Geico enjoyed a six percentage point cost advantage over Progressive in operating costs. Given that half of its business is through insurance agents, it’s unlikely that Progressive will ever catch up. But Progressive CEO Peter Lewis, who led the company from 1965 to 2000, understood that an auto insurer’s biggest cost center is the claims it must pay policyholders, in fact four to five times higher than its administrative and advertising costs. If Progressive could manage these “claims costs” better than the competition, Lewis reasoned, then it could become the de facto low-cost auto insurer.

The key to managing claims costs was technology in all its glorious variety. Back-end systems at headquarters that could analyze prices and risks for individual drivers were important, as were front-end innovations like Snapshot, a shoebox-sized device that in the 1990s Progressive began installing in willing customers’ cars. Snapshot, now an app on your mobile phone, tracks a customer’s driving behavior; more than one in three Progressive customers purchasing insurance directly from the company opt for “usage-based” premiums. Thanks to Snapshot and other innovations, Progressive simply knows more about its drivers than any other insurer, creating a virtuous cycle in which the company knows which ones to reward with discounts, which to punish with surcharges, and which to purge altogether.

So while Progressive’s operating costs have historically been six points lower than Geico’s, its loss costs have been 11 points higher, meaning Geico’s low-cost moat has been broken by technology. Unlike Progressive’s streamlined system, Geico has more than 600 legacy IT systems. He only started working on a Snapshot-like product in 2019, twenty years after Progressive started.

Buffett liked to say that when the tide goes out, you see who’s swimming naked, and COVID was the perfect storm to reveal how little attention Geico had paid to its digital wardrobe. During COVID, people suddenly stopped driving, and then when the pandemic ended, they drove more than ever and more recklessly than ever. At the same time, the worst inflation in four decades has hit all sectors of the economy, including auto repair shops. Such rapidly changing conditions favored insurers with robust tracking tools, like Progressive, and punished insurers without them, like Geico. Since 2020, Progressive has nearly doubled its number of personal auto insurance policies, but Geico has lost nearly 15% of its personal insurance base. Progressive, not Geico, is now the nation’s second-largest auto insurer.

It turns out that while gecko branding was important, it wasn’t as powerful as using sophisticated digital tools. Geico is a good example of what happens when a company, even a powerful one, fails to reinvest in its future. Rather than a virtuous cycle – technology investments leading to better prices and better products, which generate more profits, which can then be reinvested to move the cycle forward – Geico seems caught in the same vicious cycle that afflicts businesses. General enginesMacy’s and other historical companies.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com